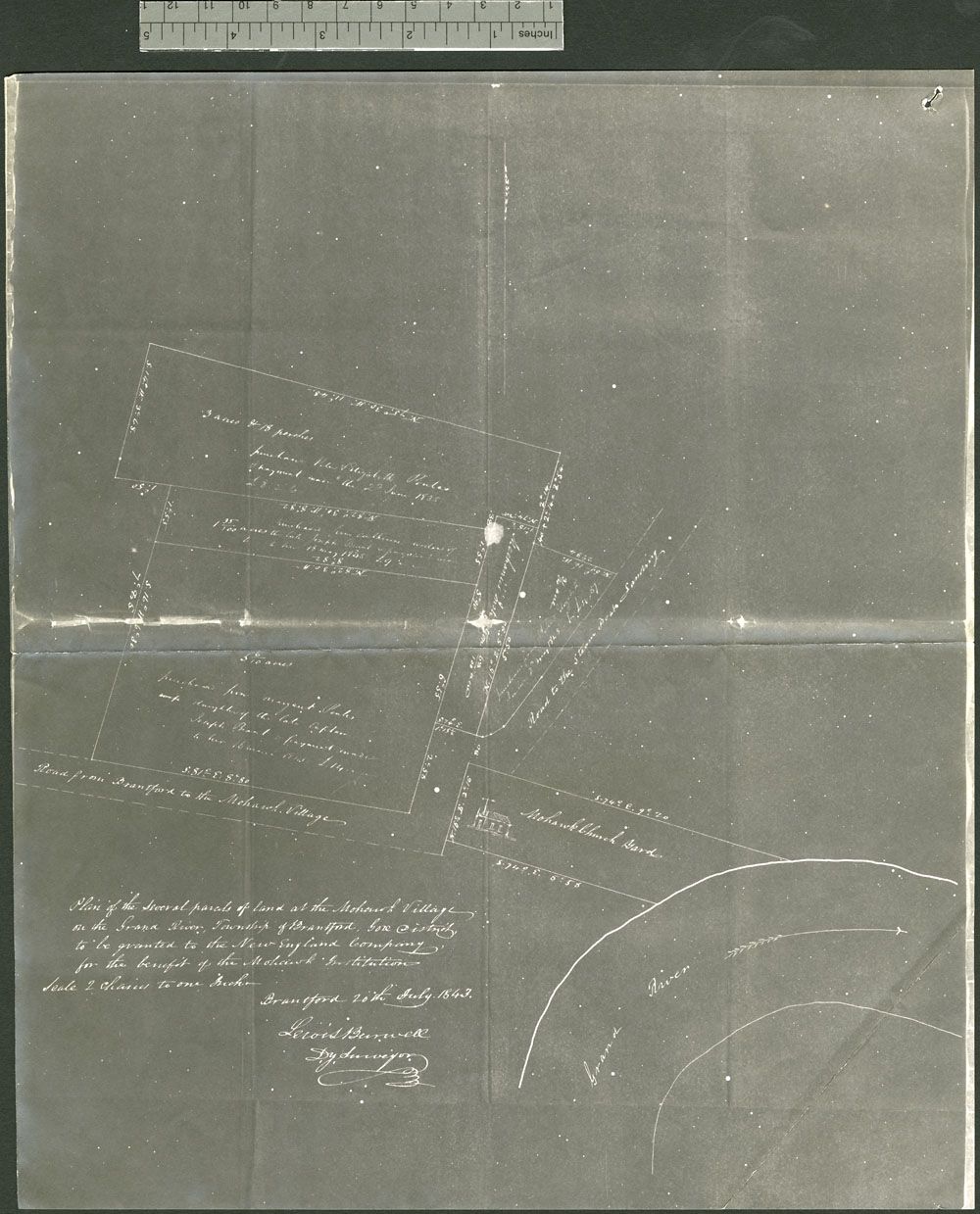

The Corporation of the City of Brantford voted in a colonial-styled meeting to sell the Arrowdale golf course, although the land is part of a questionable lease of 807-acre plot designated as a Reservation to host the influx of alien residents, a lease signed by 28 “Sachams” of the Six Nations, the plot is historically known as a white man’s reserve in local media.

After Royal eviction orders failed to vacate the squatters, a plot designated to prevent further encroachments of the Mohawk Farmlands.

Mohawk of the Grand River maintain that they possess the title to peaceably enjoy the lands forever and that they have never waived their Mohawk civil liberties or freedoms., they further maintain that that has never granted jurisdiction to any foreign alien governments, including municipalities as third party service providers pretending to be a government.

The lands are under federal lands claims processes. Yet, while Brantford released a policy on Native lands claims, asking that natives have patience while the process is ongoing, the city does not give the same level of commitment and restraint shown by the UE Mohawks, and further yet, earlier in 1994 the Brantford city mayor commissioned a lands claims report on the real-world value of the lands claimed by the city, including the 807-acre plot known as Arrowdale.

First Nations Policy (removed from website 2019, archived on waybackmachine 2014): http://www.Brantford.ca

The commission valued the land Brantford has claimed as its own at 250 billion, which the Arrowdale lands would have been designated a certain value, and this value is total risk, and the Arrowdale lands could be valued at anywhere between one dollar to 250 billion.

FourtyBee is an outlet to publish aerial photos, videos, and stories about the evolution of drone technology, documenting ongoing land encroachments; residential and commercial development. We capture images, videos and stories from landmarks to people, we research the history of Grand River Country (and beyond) from a Mohawk perspective.

However even now this is being actively covered up by city staff, city lawyers and the council, not only do they propose to gain $20 plus million from the sale of UE Mohawk lands (Haldimand tract), they will be shedding known risks forwarded by their own 1994 lands claims commission.

This is a concern for good faith, and the legal landscape of the ongoing lands claims process, by compounding the risk, selling risk, and frustrating the title to this particular parcel of land. The UE Mohawk has informed the Council of the UE Mohawk’s desire to liberate the lands and place the land into the mohawk Lands registry system.

The city council has also been put on notice that they are intermeddling with trust property and that they have by their own action have personally become liable as de facto trustee for the real party in interest to the Haldimand Pledge and Proclamation and the true beneficiaries to the Haldimand Tract., namely the UEL Mohawk descendants.

Share this video and join the campaign to Save this endangered space on Facebook “save Arrowdale”, the city of Brantford may be discriminating against and segregation the lower-income citizens, why treat this common asset and community any different from the North ridge community.

It was not long ago this was seen as a necessity for spatial equality, the green space and Winterlands need to be preserved for the coming generations, If you care about these spaces do something to show the council you care.

Write them, sing to them, make plays in their names, let the records of history show you tried, and let the record show when they fail. The harm caused by spatial inequality is quantifiable and has real-world effects on mental and physical wellbeing.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]